by Kat Kelley

Despite the oppression I face as a woman, I derive privilege from many of my identities- I am white, a member of the Georgetown community, and- on the spectrums / in the spheres of gender identity and sexual orientation- I pretty much identify and present as cisgendered and heterosexual.

I’m also pretty good at being a feminist, within my communities, but I’m pretty subpar at intersectionality. I have struggled to find my voice as an ‘ally’ on issues that affect marginalized identities that do not define me.

Thus, I’ve made an effort to shut up and education myself, two leading pieces of advice on allyship from Mia McKenzie, founding editor and editor-in-chief of Black Girl Dangerous. McKenzie argues that ally is not a valid title or identity but a “practice,” an “active thing.” She continues on to say that it is ‘exhausting’ and that it “ought to” be, “because the people who experience racism, misogyny, ableism, queerphobia, transphobia, classism, etc. are exhausted. So, why shouldn’t their ‘allies’ be?”

This piece both challenged and rejuvenated my constant regular but inconsistent attempts at allyship. I absolutely agree that I am not entitled to the term ‘ally,’ and actually prefer McKenzie’s interpretation. I fuck up at social justice all the time and often ‘retreat’ into my privilege in the name of self-care. I feel fraudulent as an ‘ally’ every time I ‘pick my battles,’ every time I decide to ignore racist, ableist, heteronormative, or gendernormative microagressions.

I certainly do not want to misrepresent McKenzie’s words; she did not explicitly say that allies are not entitled to a voice or to self-care. I did, however, interpret her words to imply that the role for allies’ voices is limited, and that self-care is a privilege for individuals not experiencing a particular kind of oppression, and that instead of seeking self-care we should resign ourselves to exhaustion.

After reading her article, I immediately felt discomfort at her words, in large part due to the fact that my approach to social justice began in 2009, when I became a sexual assault crisis counselor, speaking to survivors of sexual assault on a 24-hour crisis hotline- a position in which self-care is vital. However, being called out on your privilege is uncomfortable, and often elicits a defensive response. I thought that I may just be reacting negatively to her words because of that privilege, because of how convenient it is to retreat into my privilege when I’m exhausted, or trying to maintain a relationship, or trying to study for a midterm or when I’m trying to cope with my own experiences of oppression.

Ultimately, I think we –members of social justice movements – should recognize that for the sustainability, mainstream acceptance (which is unfortunately a pretty valuable thing), and growth of our movements, we need to make a space for part-time allies. I don’t mean that we should validate the allyship of anyone who shares the HRC equality sign on their facebook page, but if someone listens to call-outs when they fuck up, if they strive to be better allies, if they don’t actively perpetuate privilege and oppression, I want them on my team.

Why? People of privileged identities are not entitled to the safe spaces of people of marginalized identities, and they certainly aren’t entitled to a voice in those spaces. However, social justice work is complex and the roles within a given movement are diverse. We need bridge people just as much as we need radical voices that won’t budge. We need people who can do ‘translation’ work, and leverage their privilege and reach the spaces in which they are accepted due to their seemingly-less radical beliefs.

This is coming from someone who six months ago was drunk-crying to her best friend soul mate, partner in feminism, utter idol and inspiration, Erin Riordan, saying “I’m not radical enough.” But ultimately, the Erins of the world could not uproot the patriarchy alone any more than the Kats could. While Erin is unapologetic and uncompromising (weirdly enough those words, just like ‘radical’ don’t always have a positive connotation; to me they are the highest compliments I can give), I could spend hours talking to a misogynist, meeting them where they are, facilitating their break down and challenging of their own biases. While my beliefs are ‘radical’ my approaches are more mainstream, more socially palatable.

We need the Erins of the world to call out HRC for sucking at incorporating trans rights and justice into their work, and we need the HRC equality sign all over Facebook to ensure that LGBTQ-youth know that a portion of their friends support (some of) their rights, so that bigots know that they can’t get away with saying ‘faggot’ in front of many of their peers. The invalidating oversimplification of these roles would be to label them as ‘prinicpled’ vs. ‘pragmatic,’ but ultimately no movement can succeed if they forget those most marginalized or if they alienate the mainstream members of their community.

We need casual allies, we need bridge people, not to speak ‘on behalf’ of people of marginalized identities, but to work within their communities, and encourage people of their privileged identities to recognize, check, and dismantle those privileges.

While I love intra-feminist dialogue, it can be frustrating to talk with individuals who don’t self-identify as feminists and whom need convincing that feminism is relevant, who invalidate the microaggressions I regularly experience as a woman. Allies have an invaluable role to play in validating the experiences of people of marginalized identities to people of privileged identities. I don’t need a man to tell me that my experiences are valid, but other men may respond well to their peers acknowledging that my experiences are valid and that I’m not just sensitive / overreacting / hyperaware.

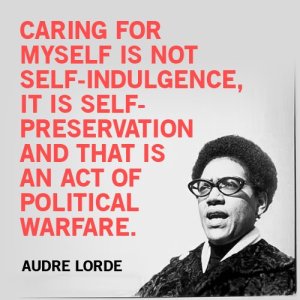

Finally, self-care is vital to the sustainability of a movement, or of an individual’s work within a movement. Radicalism is more ‘popular’ or tenable in youth because burnout is real. Nonprofits that don’t enable and encourage their employees to practice self-care see debilitating levels of employee turnover.

It’s okay to turn off your feminist lens for 30 minutes to watch TV produced in our rape culture. It’s okay to not call your uncle out for racial microaggressions because you want to enjoy Thanksgiving. It’s okay to prioritize you over ‘the’ movement every now and then. Self-care isn’t selfish, self-care is sustainable.

Recent Comments